The Science of Free Will and Behavior

Published by marco on

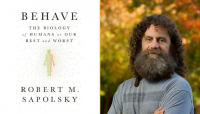

The podcast episode 134 | Robert Sapolsky on Why We Behave the Way We Do by Sean Carroll (Wondery) was a really interesting introduction/look at the science of free will as described in far greater detail in his book Behave (which I have not yet read).

Robert M. Sapolsky's BehaveI’ve included a partial transcript of the parts that I found the most interesting. The following comes from the end of the episode, where they both did an excellent job of summarizing the preceding discussion’s points as well as pointing out logical conclusions for e.g. legal proceedings. I.e. if environment and breeding and upbringing account for a large part of your default behavior—against which you can actively fight, but first you have to notice that there’s something you wish to change—then to what degree can you really be held responsible for at least some of your actions?

Robert M. Sapolsky's BehaveI’ve included a partial transcript of the parts that I found the most interesting. The following comes from the end of the episode, where they both did an excellent job of summarizing the preceding discussion’s points as well as pointing out logical conclusions for e.g. legal proceedings. I.e. if environment and breeding and upbringing account for a large part of your default behavior—against which you can actively fight, but first you have to notice that there’s something you wish to change—then to what degree can you really be held responsible for at least some of your actions?

“Carroll: Something makes me think if more people were aware of how much of our everyday behavior was not completely rational, rule-based, cognitive…and how much of it was automatic, visceral, driven by heuristics that we’ve inherited from thousands of years ago, it would cast our decisions in a slightly different light. I think a lot of people stick to their guns about their decisions because they’re convinced that they’re rational, even if they’re not and, maybe, sowing a little bit of doubt in that conviction would be a good thing.

“Sapolsky: The psychologist Josh Green at Harvard stated it really well, that, when people saying I have a right to be doing that, what they’re saying is I can only rationalize why I want to do that, I don’t actually have a rational reason. I can’t tell you why I wanna do it, but I wanna do it so much that I’m going to declare it to be right. That’s exactly a circumstance like this. In an even broader sense, if you accept that we are nothing more or less than our biology—incredibly complicated biology—from one second ago to one million years ago and interacting with environment, […] If we are nothing more or less than our biology, and those are biological influences over which we have no control, […] you can never feel justified in thinking that you are entitled to anything more than anyone else because whatever it is that you have done, which you believe has earned you praise or entitlement, you had nothing to do with, and if you really, really believe this stuff, you have no rational grounds for every hating anyone. Because they didn’t have a damned thing to do with whatever they did, no matter how horrific or hurtful it was, and if you really think those ways, this could be a very different world, and I would think those ways for about 3.5 seconds at a time […] but if you really believe this stuff, those are the only conclusions you can reach.

“Carroll: Couldn’t you just say, ‘I really like being a bundle of visceral heuristics’ and just … go with it? Lean in?

“Sapolsky: Yeah, except then you have to ask: so what are the circumstances that brought you to the point of liking being a bundle of heuristics? The legal system deciding if somebody intended to something or not and, if they intended to, you’re in trouble. They legal system never says: where did that intent come from?[1]

“That came from the combination of these seven gene variants, this thing that happened during second trimester, these cultural values during childhood or the day that they got exposed to that toxin when they were 18 and then got hit in the head.

“Carroll: Well, you know, I do appreciate your uniquely optimistic version of existential anxiety and dread.”