The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (Read in 2014)

Disclaimer: these are notes I took while reading this book. They include citations I found interesting or enlightening or particularly well-written. In some cases, I’ve pointed out which of these applies to which citation; in others, I have not. Any benefit you gain from reading these notes is purely incidental to the purpose they serve of reminding me what I once read. Please see Wikipedia for a summary if I’ve failed to provide one sufficient for your purposes. If my notes serve to trigger an interest in this book, then I’m happy for you.

Notes

The idiot is the tale of a Russian ex-patriate named Prince Lef Muishin who returns to Russia from having lived in Switzerland. He was sent to Switzerland in order to cure his chronis epilepsy, which rendered him stupefied and nearly speechless, for all intents and purposes an idiot.

He returns penniless but quickly ingratiates himself to a noble family, which agrees to take him in, if only for a while. The cast of characters surrounding him is wild and foolish and, as in so many other Russian novels, utterly and completely useless. There is almost no indication of where money comes from—it might as well just grow on trees. The others consider the prince an idiot, but he is evinces deeper philosophical thinking than the rest of them put together and is much more eloquent, to boot.

The plot is very bare, but consists of sketches, almost like theater pieces, that feels much more like the Brothers Karamazov than his earlier work, Crime and Punishment.

Dostoyevsky doesn’t waste many words on descriptions of places or people. Places have names, women are beautiful and men are distinguished, but not much else. Occasionally someone is said to have a mustache but that’s about where the descriptiveness ends. As in Karamazov, the characters ricochet from joy to abject misery within seconds, always shouting and rejoicing as if there were only exaggerated emotions. People fall in love in minutes. It’s kind of crazy, really, and sometimes hard to understand how something that reads so much like a Mexican telenovella script can be called some of the world’s best literature. There is almost no metaphor or simile in Karamazov or The Idiot.

Crime and Punishment is different. Significantly so. Here the descriptions of the environment, the characters and the situations are visceral and wonderfully done. The misery is heartrending but at least it doesn’t feel plastic and fake. There are descriptions on a par with the master of the form, Tolstoy or Twain, whose depictions of nature were absolutely lovely and similarly evoked emotion.

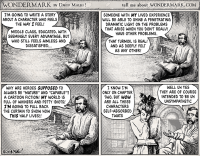

As #1074; Le Roman à Crybaby by David Malki (Wondermark) put it,

As #1074; Le Roman à Crybaby by David Malki (Wondermark) put it,

“These poor people, shoehorned by society into leading lives where they are unable to be anything but annoying.”

Citations

On the entitlement of nobility and idleness:

“The fact was, Totski was at that time a man of fifty years of age: his position was solid and respectable; his place in society had long been firmly fixed upon safe foundations; he loved himself, his personal comforts, and his position better than all the world, as every respectable gentleman should!”

“Let’s all go to my boudoir,“ she dais, “and they shall bring some coffee in there. That’s the room where we all assemble and busy ourselves as we like best,” she explained. “Alexandra, my eldest, here plays the piano, or reads or sews; Adelaida paints landscapes and portraits (bu never finishes any); and Aglaya sits and does nothing. I don’t work too much, either.”

This kind of reminds me of Sansa’s thoughts in the “Storm of Swords”, the Song of Ice and Fire series being also largely concerned with the lives of nobility.

“This woman, this human being, lived to a great age. She had children, a husband and family, friends and relations; her household was busy and cheerful; she was surrounded by smiling faces; and then suddenly they are gone, and she is left alone like a solitary fly… like a fly, cursed with the burden of her age. At last, God calls her to Himself. At sunset, on a lovely summer’s evening, my little old woman passes away—a thought, you will notice, which offers much food for reflection—and behold! Instead of tears and prayers to start her on her last journey, she has insults and jeers from a young ensign, who stands before her, with his hands in his pockets, making a terrible row about a soup tureen!”

When the Prince is the only voice of moral reason in a conversation, he is chided by those supposedly holding the moral high ground, the non-noble revolutionists.

“Prince, you are not only simple, but your simplicity is almost past the limit,“ said Lebedeff’s nephew, with a sarcastic smile.”

In a country of the blind, the one-eyed man is supposedly king, but it seems that the two-eyed man is an idiot.

In this next scene, a young man of the left has been offered financial recompense as remuneration for a perceived slight. His friend tells him the way of the world.

“Accept, Antip,” whispered the boxer eagerly, leaning past the back of Hippolyte’s chair to give his friend this piece of advice. “Take it for the present; we can see about more later on.”

A brutal slash at the supposedly honorable left, who are just as grasping as those they seek to unseat, though they couch their actions in flowery paeans to the nobility of man. These are the kind of people who will never change anything fundamental. Their main problem with the status quo is not how the status quo works or how undignifying it is for everyone involved, but that they are not on top. Once they are on top, they will lean back and enjoy all of the spoils they once derided, when those selfsame spoils were being wrested from their hands rather than being pushed into them.

This next part reminded me a bit of a part of the Brothers Karamazov, where Dmitri also had stolen money and wasted half of it, sparing the other half up painstakingly because, once he’d paid that half back, the crimes could still be forgiven, though money had been stolen and a lot of it spent. As long as half was nobly returned, it would be OK and the error could be forgiven.

“Of course, there is a difference between a hundred roubles and two hundred and fifty, but in this case the principle is the main point, and that a hundred and fifty roubles are missing is only a side issue.”

“Why did you come here tonight so insolently? ‘Give us our rights, but don’t dare to speak in our presence. Show us every mark of deepest respect, while we treat you like the scum of the earth.‘ The miscreants have written a tissue of calumny in their article, and these are the men who seek for truth, and do battle for the right! ‘We do not beseech, we demand, you will get no thanks from us, because you will be acting to satisfy your own conscience!’ What morality!”

The classic plaint against “the system”—commonly capitalism, or the peculiarly single-minded variant we employ—in which it is pointed out to those benefiting that their comfort rests atop a heap of bones and suffering.

“Not railways, properly speaking, presumptuous youth, but the general tendency of which railways may be considered as the outward expression and symbol. We hurry and push and hustle, for the good of humanity! ‘The world is becoming too noisy, too commercial!’ groans some solitary thinker. ‘Undoubtedly it is, but the noise of waggons bearing bread to starving humanity is of more value than tranquility of soul.’ replies another triumphantly, and passes on with an air of pride. As for me, I don’t believe in these waggons brining bread to humanity. For, founded on no moral principle, these may well, even in the act of carrying bread to humanity, coldly exclude a considerable portion of humanity from enjoying it; that has been seen more than once.”

Hippolyte describes why suicide is not immoral, but a way of exerting control where there is otherwise none.

“And finally, nature has so limited my capacity for work or activity of any kind, in allotting me but three weeks of time, that suicide is about the only thing left that I can begin and end in the time of my own free will.

“Perhaps then I am anxious to take advantage of my last chance of doing something for myself. A protest is sometimes no small thing.”

An old and eloquent formulation of “ignorance is bliss” and its complement, “knowledge is suffering”. I have a lovely cartoon that posits a corollary to the oft-misattributed maxim that “those who do not know or remember history are doomed to repeat it”. It reads “Those who do know history are doomed to watch others repeat it.”

I would paraphrase it as: “Those who do know history are doomed to stand by powerless which the ignorant and more powerful go about the business of repeating it.”

“Of such people there are countless numbers in this world—far more even than appear. They can be divided into two classes as all men can—that is, those of limited intellect, and those who are much cleverer. The former of these classes is the happier.

“to a commonplace man of limited intellect, for instance, nothing is simpler than to imagine himself an original character, and to revel in that belief without the slightest misgiving.

“Many of our young women have thought fit to cut their hair short, pun on blue spectacles, and call themselves Nihilists. By doing this they have been able to persuade themselves, without further trouble, that they have acquired new convictions of their own. some men have but felt some little qualm of kindness towards their fellow-men, and the fact has been quite enough to persuade them that they stand alone in the van of enlightenment and that no-one has such humanitarian feelings as they. Others have but to read an idea of somebody else’s, and they can immediately assimilate it and believe that it was a child of their own brain. The “impudence of ignorance,” if I may use the expression, is developed to a wonderful extent in such cases;—unlikely as it appears, it is met with at every turn.”

The hipster/poseur is an ancient character class, it seems. And, in the same breath, putting the lie to the youthful belief that they are inventing everything and that they are no only the first to suffer in the particular fasion in which they are suffering but also that the solution they come up with is unique in history. In all likelihood, it is not. One cannot spend ten minutes thinking about a thing and think to outstrip all of human history, ingenuity and knowledge. If you think you’re being clever, you are most likely being clever in a restricted field, you have have found a local maximum that looks like a molehill from the heights achieved by others who have hoed that particular row for much, much longer. In the field of philosophy, that row was hoed millenia before you were even born.

Do not let this prevent you from enjoying your feeling of genius. That you came up with the thought on your own is encouraging and merits further effort. You have, however, only contributed to your own personal growth and not yet added a stone to the cairn of human knowledge.

Errata

When I read books that I downloaded from Gutenberg Project, I like to be helpful and provide corrections where I can. They have a very friendly and responsive errata-submission system.

Page 282:

There I we don’t often get that sort of letter; and yet

Remove “There I” before “we”

Page 289:

The fact was that in the crowd, not far from where lie was sitting

Change “lie” to “he”; not far from where [he] was sitting

Page 293:

“What I don’t you know about it yet? He doesn’t know—imagine that!”

Remove the “I”

Page 297-298:

“he was only aware that she was sitting by, him and talking to him, and”

Remove the comma after “by”; that she was sitting by him and talking

Page 337:

The man’s face seemed tome to be refined and even pleasant.

Change “tome” to “to” and “me”; The man’s face seemed to me to be

Page 403:

“He’s a little screw,” cried the general: “he drills holes my heart […]”

Add “in” after “holes”; he drills holes [in] my heart

Page 411–412:

He would take up a hook from the table and open it

Change “hook” to “book”; He would take up a [book] from the table

Page 433:

bought with his money, instead of Schiosser’s History.

Change “Schiosser’s” to “Schlosser’s”

Page 464:

We must let out Christ shine forth upon the Western nations,

Change “out” to “our”; We must let [our] Christ shine

Page 467:

it seemed to be uncertain whether or no to topple over on to the head

Change “no” to “not”; whether or no[t] to topple over

Page 510:

he whipped up the horses, and they were oft.

Change “oft” to “off”; and they were [off].

Page 527:

infatuations and adventures, that they did hot care to talk of them,

Change “hot” to “not”; that they did [not] care to talk of them,