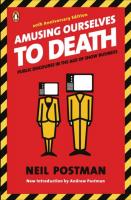

Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman (1984) (read in 2021)

Published by marco on

Standard disclaimer[1]

This book explores the thesis that printed material is the sweet spot for delivering information to human beings. The move in the mid-twentieth century to audiovisual presentation is a step in the wrong direction. The medium of television transforms everything it touches into entertainment. The book was written in 1985 and deals with the hole punched in culture by television.

This book explores the thesis that printed material is the sweet spot for delivering information to human beings. The move in the mid-twentieth century to audiovisual presentation is a step in the wrong direction. The medium of television transforms everything it touches into entertainment. The book was written in 1985 and deals with the hole punched in culture by television.

Thirty-seven years later, the direness of the situation has been turned up several notches, with the advent of the kind of Internet that we of course ended up with, thanks to our mad form of capitalism that absorbs everything it touches. The state of information is more insane, incomprehensible, and superficial than ever.

It is a world where ignorance is bliss. The less you understand of the firehose of information and propaganda fired at you, the better.

“In watching American television, one is reminded of George Bernard Shaw’s remark on his first seeing the glittering neon signs of Broadway and 42nd Street at night. It must be beautiful, he said, if you cannot read.”

It’s like when I have to suffer through Britney Spears because I understand the lyrics, but I can enjoy similarly catchy pop music in a foreign language. You’re able to appreciate the rhythm and melody without being distracted by the largely insipid content.

He laments the loss of the primacy of radio, which he considers to have been superior to television because it doesn’t have the seductive visual component.

“No one turns on radio anymore for soap operas or a presidential address (if a television set is at hand). But everyone goes to television for all these things and more, which is why television resonates so powerfully throughout the culture.”

But radio these days has been completely destroyed by the same capitalism that’s to blame for the grip that television once had everyone’s attention. Clear Channel owns everything, the whole business is a cartel, and there is no room for anything like useful information.

The Internet has definitely made space for all kinds online to get exposure. In that sense, communication has been democratized. Even the ugly find audiences because they are allowed to search without being a priori filtered out. Podcasts and audio books are very popular now, as well. Although it’s unclear what percentage they are relative to TikTok (probably super-low; no-one reads anymore). Even popular SubStacks now offer “listen to this article”.

“It is simply not possible to convey a sense of seriousness about any event if its implications are exhausted in less than one minute’s time. In fact, it is quite obvious that TV news has no intention of suggesting that any story has any implications, for that would require viewers to continue to think about it when it is done and therefore obstruct their attending to the next story that waits panting in the wings.”

Whereas the media used to avoid lingering too long, it’s now changed quite a bit. With the advent of 24h news (something Postman didn’t foresee at all), they now belabor a story to death. Also, now, we have the ability to pause and replay and reflect. If we take this opportunity, then we can use television for our own purposes, rather than be used by it. Most don’t, though.

The following, though, is an example of Postman putting too much faith into what he thinks are reliable news sources. It’s always been bullshit propaganda, but he tries very hard to make it look more serious than it had any right to be treated.

“The viewers also know that no matter how grave any fragment of news may appear (for example, on the day I write a Marine Corps general has declared that nuclear war between the United States and Russia is inevitable) […]”

That’s not news, that’s hearsay. He’s confusing gravity for truth. If people ignore it, it might be not that they don’t care, but that they know that official sources are horseshit. I feel that his thesis is sound, but that his examples are superficial and lacking in conclusiveness, which gravely undermines the thesis, if those are the only examples he can come up with.

A little while later, he has a decidedly staid take on the gravity of news—seeming to imply that every tragic tale we hear should be taken seriously, when the media dredge up one tale of woe after another to manipulate our empathy.

“In watching television news, they, more than any other segment of the audience, are drawn into an epistemology based on the assumption that all reports of cruelty and death are greatly exaggerated and, in any case, not to be taken seriously or responded to sanely.”

Perhaps, in Postman’s time, there was a lot less of this manipulation, but nowadays it’s become the main form of content. To ignore it is the correct response. Television news is useless as a source of fact. That’s not what it’s for. There’s no need to lament it. People don’t really want to be informed, they certainly don’t want to read. I don’t think he examines enough why things are this way, that people had to be trained to stop caring about anything that matters, had to be trained to think that what’s doesn’t matter does.

He never quite gets around to addressing the corruptive influence of capitalism and market forces on information-dissemination to an informed public.

He also seems to be misled by the reporters who blame their lack of coverage on their listeners, when it is they who determine what people want, or at least their bosses. Cart before the horse. Maybe the NYT was different then, but this sounds suspiciously exactly like the same shit they pull today.

He’s also unfortunately quite condescending to the people that he claims to be trying to save—his fellow Americans.

“Today, on television commercials, propositions are as scarce as unattractive people. The truth or falsity of an advertiser’s claim is simply not an issue. A McDonald’s commercial, for example, is not a series of testable, logically ordered assertions. It is a drama—a mythology, if you will—of handsome people selling, buying and eating hamburgers, and being driven to near ecstasy by their good fortune.”

Part of this is also that commercials aim to separate a large group of people from their disposable income. That group didn’t used to be as large as it is now. Nor did we hear about them all the time. We hear about fools buying NFTs of sneakers as if we could be them. We travel in very different circles from the other 95%.

“As I write, the trend in call-in shows is for the “host” to insult callers whose language does not, in itself, go much beyond humanoid grunting. Such programs have little content, as this word used to be defined, and are merely of archeological interest in that they give us a sense of what a dialogue among Neanderthals might have been like.”

This sounds more like the precursor to today’s liberal snobbery than reasoned criticism. Compare again to someone like Chris Hedges, who does not descend to this ad-hominem level. He doesn’t stop there with his disdain of the hoi polloi. In another example, he mocks the obsession with “trivia”, as in the rise of the game of Trivial Pursuit. This is pretty arrogant horseshit. I think he’s taking it a bit too far. He sounds like a giant fucking stick in the mud who has carefully avoided learning ephemera but also interacting with people. To what end?

In the end, the author sounds very conservative, almost reactionary. He has no sense of humor and doesn’t see at all how levity can mix with serious information. He would have hated Bill Hicks, who was a poet of incisive commentary. Hicks said with a few words what a bloviator would say with pages.

I personally think think that part of this guy’s inspiration was that he was mad that no-one thought he was funny. His attempts at humor are so dry that they’ve been wrung completely free of wit. Chris Hedges wrote the foreword to Lee Camp’s book. That strikes a better balance.

Citations

“Today’s eighteen-to-twenty-two-year-olds live in a vastly different media environment from the one that existed in 1985. Their relationship to TV differs. Back then, MTV was in its late infancy. Today, news scrolls and corner-of-the-screen promos and “reality” shows and infomercials and nine hundred channels are the norm. And TV no longer dominates the media landscape.”

And fifteen years later, it’s all been turned up a notch, more insane, incomprehensible, and superficial than ever.

““Screen time” also means hours spent in front of the computer, video monitor, cell phone, and handheld. Multitasking is standard. Communities have been replaced by demographics. Silence has been replaced by background noise. It’s a different world.”

“Maria noted that the oversimplification and thinking “fragmentation” promoted by TV-watching may have contributed to our Red State/ Blue State polarization.”

Even worse fifteen years later.

“His questions can be asked about all technologies and media. What happens to us when we become infatuated with and then seduced by them? Do they free us or imprison us? Do they improve or degrade democracy? Do they make our leaders more accountable or less so? Our system more transparent or less so? Do they make us better citizens or better consumers? Are the trade-offs worth it?”

“We were keeping our eye on 1984. When the year came and the prophecy didn’t, thoughtful Americans sang softly in praise of themselves. The roots of liberal democracy had held. Wherever else the terror had happened, we, at least, had not been visited by Orwellian nightmares.”

“Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny “failed to take into account man’s almost infinite appetite for distractions.””

“It is an argument that fixes its attention on the forms of human conversation, and postulates that how we are obliged to conduct such conversations will have the strongest possible influence on what ideas we can conveniently express. And what ideas are convenient to express inevitably become the important content of a culture.”

“A person who reads a book or who watches television or who glances at his watch is not usually interested in how his mind is organized and controlled by these events, still less in what idea of the world is suggested by a book, television, or a watch.”

“[…] the clock introduced a new form of conversation between man and God, in which God appears to have been the loser. Perhaps Moses should have included another Commandment: Thou shalt not make mechanical representations of time.”

“We do not see nature or intelligence or human motivation or ideology as “it” is but only as our languages are. And our languages are our media. Our media are our metaphors. Our metaphors create the content of our culture.”

“I mean only to call attention to the fact that there is a certain measure of arbitrariness in the forms that truth-telling may take. We must remember that Galileo merely said that the language of nature is written in mathematics. He did not say everything is. And even the truth about nature need not be expressed in mathematics. For most of human history, the language of nature has been the language of myth and ritual.”

“In saying this, I am not making a case for epistemological relativism. Some ways of truth-telling are better than others, and therefore have a healthier influence on the cultures that adopt them. Indeed, I hope to persuade you that the decline of a print-based epistemology and the accompanying rise of a television-based epistemology has had grave consequences for public life, that we are getting sillier by the minute.”

“In a print culture, the memorization of a poem, a menu, a law or most anything else is merely charming. It is almost always functionally irrelevant and certainly not considered a sign of high intelligence.”

“My argument is limited to saying that a major new medium changes the structure of discourse; it does so by encouraging certain uses of the intellect, by favoring certain definitions of intelligence and wisdom, and by demanding a certain kind of content—in a phrase, by creating new forms of truth-telling. I will say once again that I am no relativist in this matter, and that I believe the epistemology created by television not only is inferior to a print-based epistemology but is dangerous and absurdist.”

“I will try to demonstrate that as typography moves to the periphery of our culture and television takes its place at the center, the seriousness, clarity and, above all, value of public discourse dangerously declines. On what benefits may come from other directions, one must keep an open mind.”

“The Dunkers came close here to formulating a commandment about religious discourse : Thou shalt not write down thy principles, still less print them, lest thou shall be entrapped by them for all time.”

“Among the few who understood this consequence was Henry David Thoreau, who remarked in Walden that “We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate…. We are eager to tunnel under the Atlantic and bring the old world some weeks nearer to the new; but perchance the first news that will leak through into the broad flapping American ear will be that Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough.””

Omg he gets it. He gets Twitter.

“The telegraph may have made the country into “one neighborhood,” but it was a peculiar one, populated by strangers who knew nothing but the most superficial facts about each other.”

Plus ça change, plus c’est la meme chose.

“The last refuge is, of course, giving your opinion to a pollster, who will get a version of it through a desiccated question, and then will submerge it in a Niagara of similar opinions, and convert them into—what else?—another piece of news. Thus, we have here a great loop of impotence: The news elicits from you a variety of opinions about which you can do nothing except to offer them as more news, about which you can do nothing.”

“You will, in fact, have “learned” nothing (except perhaps to avoid strangers with photographs), and the illyx will fade from your mental landscape as though it had never been. At best you are left with an amusing bit of trivia, good for trading in cocktail party chatter or solving a crossword puzzle, but nothing more.”

This is pretty arrogant horseshit. I think he’s taking it a bit too far. He sounds like a giant fucking stick in the mud who has carefully avoided learning ephemera but also interacting with people. To what end?

“Our culture’s adjustment to the epistemology of television is by now all but complete; we have so thoroughly accepted its definitions of truth, knowledge, and reality that irrelevance seems to us to be filled with import, and incoherence seems eminently sane.”

“What is television? What kinds of conversations does it permit? What are the intellectual tendencies it encourages? What sort of culture does it produce?”

“In watching American television, one is reminded of George Bernard Shaw’s remark on his first seeing the glittering neon signs of Broadway and 42nd Street at night. It must be beautiful, he said, if you cannot read.”

It’s like hearing Britney Spears or other pop music in a foreign language. You’re able to appreciate the rhythm and melody without being distracted by the largely insipid content.

“what I am claiming here is not that television is entertaining but that it has made entertainment itself the natural format for the representation of all experience. Our television set keeps us in constant communion with the world, but it does so with a face whose smiling countenance is unalterable. The problem is not that television presents us with entertaining subject matter but that all subject matter is presented as entertaining, which is another issue altogether.”

“When a television show is in process, it is very nearly impermissible to say, “Let me think about that” or “I don’t know” or “What do you mean when you say … ?” or “From what sources does your information come?” This type of discourse not only slows down the tempo of the show but creates the impression of uncertainty or lack of finish. It tends to reveal people in the act of thinking, which is as disconcerting and boring on television as it is on a Las Vegas stage.”

“It is in the nature of the medium that it must suppress the content of ideas in order to accommodate the requirements of visual interest; that is to say, to accommodate the values of show business.”

I’m not sure whether he’s mixing up cause and effect here. There are chemical reasons that have nothing to do with medium. Take Dan Brown, for instance. Or any of the most popular books today. We know more about brain chemistry than we used to.

“No one turns on radio anymore for soap operas or a presidential address (if a television set is at hand). But everyone goes to television for all these things and more, which is why television resonates so powerfully throughout the culture.”

Podcasts and audio books are very popular now. Although it’s unclear what percentage they are relative to TikTok (probably super-low; no-one reads anymore). Even popular SubStacks now offer “listen to this article”.

“Whereas the latter believes that you don’t have to be boring to be holy, the former apparently believes you don’t have to be holy at all.”

The author is very conservative, almost reactionary. He has no sense of humor and doesn’t see at all how levity can mix with serious information. He would haved hated Bill Hicks, who was a poet of incisive commentary. He said with a few words what a bloviator would say with pages.

“So far as I know, it has been used only once before in a classroom: Hegel tried it several times in demonstrating how the dialectical method works.”

I think this guy’s mad that no-one thinks he’s funny. His attempts at humor are so dry that they’ve been wrung completely free of wit. Chris Hedges wrote the foreword to Lee Camp’s book. That strikes a better balance.

“Those who apply would, in fact, submit to you their eight-by-ten glossies, from which you would eliminate those whose countenances are not suitable for nightly display. This means that you will exclude women who are not beautiful or who are over the age of fifty, men who are bald, all people who are overweight or whose noses are too long or whose eyes are too close together.”

It’s still kind of like this, but the Internet has definitely made space for all kinds online to get exposure. In that sense, communication has been democratized. Even the ugly find audiences because they are allowed to search without being a priori filtered out.

“This is a matter of considerable importance, for it goes beyond the question of how truth is perceived on television news shows. If on television, credibility replaces reality as the decisive test of truth-telling, political leaders need not trouble themselves very much with reality provided that their performances consistently generate a sense of verisimilitude.”

“It is simply not possible to convey a sense of seriousness about any event if its implications are exhausted in less than one minute’s time. In fact, it is quite obvious that TV news has no intention of suggesting that any story has any implications, for that would require viewers to continue to think about it when it is done and therefore obstruct their attending to the next story that waits panting in the wings.”

This has changed quite a bit with the advent of 24h news. Now they belabor a story to death. Also, now, we have the ability to pause and replay and reflect. If we take this opportunity, then we can use television for our own purposes, rather than be used by it.

“The viewers also know that no matter how grave any fragment of news may appear (for example, on the day I write a Marine Corps general has declared that nuclear war between the United States and Russia is inevitable),”

That’s not news, that’s hearsay, fuckwit. Don’t confuse gravity for truth. If people ignore it, it might be not that they don’t care, but that they know that official sources arehorseshit. I feel that his thesis is sound, but that his examples are superficial and lacking in conclusiveness, which gravely undermines the thesis, if those are the only examples he can come up with.

“Imagine what you would think of me, and this book, if I were to pause here, tell you that I will return to my discussion in a moment, and then proceed to write a few words in behalf of United Airlines or the Chase Manhattan Bank. You would rightly think that I had no respect for you and, certainly, no respect for the subject. And if I did this not once but several times in each chapter, you would think the whole enterprise unworthy of your attention.”

Very good! Great analogy.

“We have become so accustomed to its discontinuities that we are no longer struck dumb, as any sane person would be, by a newscaster who having just reported that a nuclear war is inevitable goes on to say that he will be right back after this word from Burger King; who says, in other words, “Now … this.” One can hardly overestimate the damage that such juxtapositions do to our sense of the world as a serious place.”

“In watching television news, they, more than any other segment of the audience, are drawn into an epistemology based on the assumption that all reports of cruelty and death are greatly exaggerated and, in any case, not to be taken seriously or responded to sanely.”

That is the correct lesson to draw, though. Television news is useless as a source of fact. That’s not what it’s for. No need to lament it. Also, people don’t really want to be informed, they certainly don’t want to read. I don’t think he examines enough WHY things are this way.

“By television’s standards, the audience is minuscule, the program is confined to public-television stations, and it, is a good guess that the combined salary of MacNeil and Lehrer is one-fifth of Dan Rather’s or Tom Brokaw’s.”

Here would be the ideal place to address the corruptive influence of capitalism and market forces on onformation dissemination to an informed public.

“What is happening here is that television is altering the meaning of “being informed” by creating a species of information that might properly be called disinformation. I am using this word almost in the precise sense in which it is used by spies in the CIA or KGB. Disinformation does not mean false information. It means misleading information—misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented or superficial information—information that creates the illusion of knowing something but which in fact leads one away from knowing. In saying this, I do not mean to imply that television news deliberately aims to deprive Americans of a coherent, contextual understanding of their world. I mean to say that when news is packaged as entertainment, that is the inevitable result. And in saying that the television news show entertains but does not inform, I am saying something far more serious than that we are being deprived of authentic information. I am saying we are losing our sense of what it means to be well informed. Ignorance is always correctable. But what shall we do if we take ignorance to be knowledge?”

“Walter Lippmann, for example, wrote in 1920: “There can be no liberty for a community which lacks the means by which to detect lies.””

“But this case refutes his assumption. The reporters who cover the White House are ready and able to expose lies, and thus create the grounds for informed and indignant opinion. But apparently the public declines to take an interest. To press reports of White House dissembling, the public has replied with Queen Victoria’s famous line: “We are not amused.””

I think here he is misled by the reporters who blame their lack of coverage on their listeners, when it is they who determine what people want. Cart before the horse. Maybe the NYT was different then, but this suspiciously exactly like the same shit they pull today.

“The only thing to be amused about is the bafflement of reporters at the public’s indifference. There is an irony in the fact that the very group that has taken the world apart should, on trying to piece it together again, be surprised that no one notices much, or cares.”

“The President does not have the press under his thumb. The New York Times and The Washington Post are not Pravda; the Associated Press is not Tass. And there is no Newspeak here. Lies have not been defined as truth nor truth as lies. All that has happened is that the public has adjusted to incoherence and been amused into indifference.”

“Huxley grasped, as Orwell did not, that it is not necessary to conceal anything from a public insensible to contradiction and narcoticized by technological diversions.”

“In presenting news to us packaged as vaudeville, television induces other media to do the same, so that the total information environment begins to mirror television.”

“When her audiences are shown in reaction shots, they are almost always laughing. As a consequence, it would be difficult to distinguish them from audiences, say, at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, except for the fact that they have a slightly cleaner, more wholesome look.”

Oh dear, your prejudice is showing.

“As I write, the trend in call-in shows is for the “host” to insult callers whose language does not, in itself, go much beyond humanoid grunting. Such programs have little content, as this word used to be defined, and are merely of archeological interest in that they give us a sense of what a dialogue among Neanderthals might have been like.”

Jesus. This sounds more like the precursor to today’s liberal snobbery than reasoned criticism. Compare again to Hedges, who does not descend to this ad-hominem level.

“To achieve this goal, the most modern methods of marketing and promotion are abundantly used, such as offering free pamphlets, Bibles and gifts, and, in Jerry Falwell’s case, two free “Jesus First” pins.”

Nowadays, they sell themselves more cheaply: for NFTs.

“By substituting images for claims, the pictorial commercial made emotional appeal, not tests of truth, the basis of consumer decisions. The distance between rationality and advertising is now so wide that it is difficult to remember that there once existed a connection between them. Today, on television commercials, propositions are as scarce as unattractive people. The truth or falsity of an advertiser’s claim is simply not an issue. A McDonald’s commercial, for example, is not a series of testable, logically ordered assertions. It is a drama—a mythology, if you will—of handsome people selling, buying and eating hamburgers, and being driven to near ecstasy by their good fortune.”

Part of this is also that commercials aim to separate a large group of people from their disposable income. That group didn’t used to be as large as it is now. Nor did we hear about them all the time. We hear about fools buying NFTs of sneakers as if we could be them. We travel in very different circles.

“What the advertiser needs to know is not what is right about the product but what is wrong about the buyer. And so, the balance of business expenditures shifts from product research to market research. The television commercial has oriented business away from making products of value and toward making consumers feel valuable,”

“Terence Moran, I believe, lands on the target in saying that with media whose structure is biased toward furnishing images and fragments, we are deprived of access to an historical perspective.”

This hypothesis is belied by a wealth of (often, manipulative) documentaries. But books manipulate history, as well, though, admittedly, perhaps not as immediately successfully.

“But the Founding Fathers did not foresee that tyranny by government might be superseded by another sort of problem altogether, namely, the corporate state, which through television now controls the flow of public discourse in America. I raise no strong objection to this fact (at least not here) and have no intention of launching into a standard-brand complaint against the corporate state. I merely note the fact with apprehension,”

Keeps the book shorter.

“Television does not ban books, it simply displaces them.”

“Censorship, after all, is the tribute tyrants pay to the assumption that a public knows the difference between serious discourse and entertainment—and cares. How delighted would be all the kings, czars and führers of the past (and commissars of the present) to know that censorship is not a necessity when all political discourse takes the form of a jest.”

“I don’t mean to imply that the situation is a result of a conspiracy or even that those who control television want this responsibility. I mean only to say that, like the alphabet or the printing press, television has by its power to control the time, attention and cognitive habits of our youth gained the power to control their education.”

“[…] There exists no evidence that students who were required to view “Watch Your Mouth” increased their competence in the use of the English language.”

“There exists no evidence” because it didn’t work or because they didn’t measure?

“When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people become an audience and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility.”

“In the first place, not everyone believes a cure is needed, and in the second, there probably isn’t any. But as a true-blue American who has imbibed the unshakable belief that where there is a problem, there must be a solution, I shall conclude with the following suggestions.”

“Americans will not shut down any part of their technological apparatus, and to suggest that they do so is to make no suggestion at all.”

“Television, as I have implied earlier, serves us most usefully when presenting junk-entertainment ; it serves us most ill when it co-opts serious modes of discourse—news, politics, science, education, commerce, religion—and turns them into entertainment packages. We would all be better off if television got worse, not better. “The A-Team” and “Cheers” are no threat to our public health. “60 Minutes,” “Eye-Witness News” and “Sesame Street” are.”

“To ask is to break the spell. To which I might add that questions about the psychic, political and social effects of information are as applicable to the computer as to television. Although I believe the computer to be a vastly overrated technology, I mention it here because, clearly, Americans have accorded it their customary mindless inattention; which means they will use it as they are told, without a whimper.”

So wrong and so right.

“Until, years from now, when it will be noticed that the massive collection and speed-of-light retrieval of data have been of great value to large-scale organizations but have solved very little of importance to most people and have created at least as many problems for them as they may have solved.”

“In order to command an audience large enough to make a difference, one would have to make the programs vastly amusing, in the television style. Thus, the act of criticism itself would, in the end, be co-opted by television. The parodists would become celebrities, would star in movies, and would end up making television commercials.”

“For in the end, he was trying to tell us that what afflicted the people in Brave New World was not that they were laughing instead of thinking, but that they did not know what they were laughing about and why they had stopped thinking.”