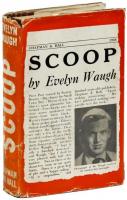

Scoop by Evelyn Waugh (1938) (read in 2022)

Standard disclaimer[1]

This is the story of the press in Great Britain in the 1930s. It paints a decidedly unflattering picture of the entire industry, one that, however hard we would try to claim to the contrary, fits extremely well in describing the media and journalistic culture in this, nearly the end of the first quarter of the 21st century. It is beautifully written, biting satire.

This is the story of the press in Great Britain in the 1930s. It paints a decidedly unflattering picture of the entire industry, one that, however hard we would try to claim to the contrary, fits extremely well in describing the media and journalistic culture in this, nearly the end of the first quarter of the 21st century. It is beautifully written, biting satire.

Suffice it to say that absolutely no-one is in any way interested in what actually happened or what the truth of a particular situation or event might be. Lord Copper runs a large newspaper. He is friends with socialite Mrs. Stitch, who is beautiful and a force of chaos in London. She is friends with John Courtenay Boot, a handsome young man with pretensions of becoming a writer or a journalist or someone famous for writing, at any rate.

He represents that part of the press—which has since because a nearly exclusive majority—that comes from an elite background and finds that telling others what to think seems like a pretty good way to earn a living. To be fair, Boot seems like a reasonably nice guy, but it’s unavoidable that he feels entitled, due to his privileged background, to employment in something associated with letters and leisure.

Lord Copper, however, mixes up John Boot—someone who’s never worked as a journalist—with William Boot, someone who publishes a bucolic bi-weekly column in his newspaper.

William lives in what is called “genteel” poverty. The entire family lives in a manor on lands that they own, but the majority of the wealth resides with a nearly insane—and nearly immortal—dowager-heiress who manipulates the rest of the family with tempting tales of impending inheritance. No-one in the household works in anything approaching a societally useful capacity and they think nothing of it. They are, in the most basic sense of the word, entitled. Because they have a title, they do not need to provide additional value.

“'I aches,‘ said Mrs Jackson with simple dignity. ‘I aches terrible all round the sit-upon. It’s the damp.‘”

Lord Copper sends William Boot to Ishmaelia, a fictional country in Northeastern Africa, to report on the impending revolution there, provoked by those dirty Bolsheviks and Marxists who’d been riled up by those dastardly Russians. Every other country is there as well, but they, of course, are on the side of good.

“But of course it’s really a war between Russia and Germany and Italy and Japan who are all against one another on the patriotic side.”

Plus ça change. We are really a tedious and unimaginative species.

Boot had only rarely left his manor’s grounds, to say nothing of having left the country. He finds the train journey from the north country to London nearly insurmountable. He is woefully unprepared for his assignment.

Boot stumbles—in the manner of an Inspector Clouseau or whatever character Leslie Nielsen played in the Naked Gun films—from one hopeless naive and ignorant misstep to another into actually ending up getting a scoop on the war there. This is an achievement because there actually isn’t a war going on, but the surfeit of journalists who are being paid to be there see it as their duty to imagine one, and to stiffen the spines of a British populace that might otherwise be less willing to part with its hard-earned taxes on military support for a country that wouldn’t, in reality, need it.

“You’ll be surprised to find how far the war correspondents keep from the fighting. Why Hitchcock reported the whole Abyssinia campaign from Asmara and gave us some of the most colourful, eyewitness stuff we ever printed.”

After having spent some time with other journalists—all of whom are hilariously and scathingly described as utterly amoral scoundrels, interested only in drinking and easy money—William ends up being the only journalist who doesn’t travel to a location that is utterly uninteresting journalistically and happens to be around to learn something that he can unknowingly report as true (even though that ends up not being what was reported as well).

William returns to London with his scoop, but the credit ends up going to John, who had never been to Ishmaelia nor had he ever filed a newspaper article. William is nonetheless relieved because now he can return to his idle and societally useless, but thoroughly entitled life in the countryside, away from stress and away from any events that may impact the rigid structure of the quotidian for him.

Citations

“You see he’s a communist. Most of the staff of The Twopence are–they’re University men, you see. Pappenhacker says that every time you are polite to a proletarian you are helping to bolster up the capitalist system. He’s very clever of course, but he gets rather unpopular.‘”

That is lovely.

“’You’ll be surprised to find how far the war correspondents keep from the fighting. Why Hitchcock reported the whole Abyssinia campaign from Asmara and gave us some of the most colourful, eyewitness stuff we ever printed. In any case your life will be insured by the paper for five thousand pounds.”

Again, gorgeous.

“[…] fringed outside with ivy, brushed by the boughs of a giant monkey-puzzle;”

“'Yes, but it’s not quite as easy as that. You see they are all negroes. And the fascists won’t be called black because of their racial pride, so they are called White after the White Russians. And the Bolshevists want to be called black because of their racial pride. So when you say black you mean red, and when you mean red you say white and when the party who call themselves blacks say traitors they mean what we call blacks, but what we mean when we say traitors I really couldn’t tell you.”

“But of course it’s really a war between Russia and Germany and Italy and Japan who are all against one another on the patriotic side.”

Plus ça change.

“'Then why do they want to send me?’

“‘All the papers are sending specials.’

“‘And all the papers have reports from three or four agencies?’

“‘Yes.’

“‘But if we all send the same thing it seems a waste.’

“‘There would soon be a row if we did.’

“‘But isn’t it very confusing if we all send different news?’

“‘It gives them a choice. They all have different policies so of course they have to give different news.’”

“News is what a chap who doesn’t care much about anything wants to read. And it’s only news until he’s read it. After that it’s dead. We’re paid to supply news. If someone else has sent a story before us, our story isn’t news. Of course there’s colour. Colour is just a lot of bull’s-eyes about nothing. It’s easy to write and easy to read but it costs too much in cabling so we have to go slow on that. See?’”

“‘…syndicated all over America. Gets a thousand dollars a week. When he turns up in a place you can bet your life that as long as he’s there it’ll be the news centre of the world.”

“‘Why, once Jakes went out to cover a revolution in one of the Balkan capitals. He overslept in his carriage, woke up at the wrong station, didn’t know any different, got out, went straight to a hotel, and cabled off a thousand word story about barricades in the streets, flaming churches, machine guns answering the rattle of his typewriter as he wrote, a dead child, like a broken doll, spreadeagled in the deserted roadway below his window–you know. ‘Well they were pretty surprised at his office, getting a story like that from the wrong country, but they trusted Jakes and splashed it in six national newspapers. That day every special in Europe got orders to rush to the new revolution. They arrived in shoals. Everything seemed quiet enough but it was as much as their jobs were worth to say so, with Jakes filing a thousand words of blood and thunder a day. So they chimed in too. Government stocks dropped, financial panic, state of emergency declared, army mobilized, famine, mutiny and in less than a week there was an honest to God revolution under way, just as Jakes had said. There’s the power of the Press for you.

“‘They gave Jakes the Nobel Peace Prize for his harrowing descriptions of the carnage–but that was colour stuff.’”

“[…] the custom had grown up for the receiving officer and the Jackson candidate to visit in turn such parts of the Republic as were open to travel, and entertain the neighbouring chiefs to a six days banquet at their camp, after which the stupefied aborigines recorded their votes in the secret and solemn manner prescribed by the constitution.”

This is not dissimilar to elections in the States. The “stupefied” part especially.

“[…] there was, moreover, a railway to the Red Sea coast, bringing a steady stream of manufactured imports which relieved the Ishmaelites of the need to practise their few clumsy crafts, while the adverse trade balance was rectified by an elastic system of bankruptcy law.”

“'Then what are you sending?’ asked Corker.

“‘Colour stuff,’ said Pigge, with great disgust. ‘Preparations in the threatened capital, soldiers of fortune, mystery men, foreign influences, volunteers… there isn’t any hard news. The fascist headquarters are up country somewhere in the mountains. No one knows where. They’re going to attack when the rain stops in about ten days. You can’t get a word out of the government. They won’t admit there is a crisis.‘”

They’ve always made shit up.

“'I aches,‘ said Mrs Jackson with simple dignity. ‘I aches terrible all round the sit-upon. It’s the damp.‘”

“The milch-goat looked up from her supper of waste-paper; her perennial optimism quickened within her, and swelled to a great and mature confidence; all day she had shared the exhilaration of the season, her pelt had glowed under the newborn sun; deep in her heart she too had made holiday, had cast off the doubts of winter and exulted among the crimson flowers; all day she had dreamed gloriously; now in the limpid evening she gathered her strength, stood for a moment rigid, quivering from horn to tail; then charged, splendidly, irresistibly, triumphantly; the rope snapped and the welter-weight champion of the Adventist University of Alabama sprawled on his face amid the kitchen garbage.”

“Might must find a way. Not “Force” remember; other nations use “force”; we Britons alone use “Might”. Only one thing can set things light–sudden and extreme violence, or better still, the effective threat of it. I am committed to very considerable sums in this little gamble and, alas, our countrymen are painfully tolerant nowadays of the losses of their financial superiors. One sighs for the days of Pam or Dizzy. I possess a little influence in political quarters but it will strain it severely to provoke a war on my account. Some semblance of popular support, such as your paper can give, would be very valuable… But I dislike embarrassing my affairs with international issues.”

“[…] on a hundred lines reporters talked at cross purposes; sub-editors busied themselves with their humdrum task of reducing to blank nonsense the sheaves of misinformation which whistling urchins piled before them;”

“But you do think it’s a good way of training oneself–inventing imaginary news?’

“‘None better,’ said William.”

“And now he stood under the porch, sweating, blistered, nettle-stung, breathless, parched, dizzy, dead-beat and dishevelled, with his bowler hat in one hand and umbrella in the other, leaning against a stucco pillar waiting for someone to open the door. Nobody came. He pulled again at the bell; there was no responsive spring, no echo in the hall beyond. No sound broke the peace of the evening save, in the elms that stood cumbrously on every side, the crying of the rooks and, not unlike it but nearer at hand, directly it seemed over Mr Salter’s head, a strong baritone decanting irregular snatches of sacred music.”

“[…] he remembered it as a treble solo rising to the dim vaults of the school chapel, touching the toughest adolescent hearts; he remembered it imperfectly but with deep emotion.”

“'William’s friend,‘ said Mrs Boot gravely, ‘has arrived in a most peculiar condition.’

“‘I know. I watched him come up the drive. Reelin’ all over the shop.‘”